Here we go again, you may be moaning as a painful situation rears its ugly head one. more. time. Perhaps you’ve prayed for a miracle for years, decades, even a lifetime. Maybe you’re exhausted from asking God to answer a prayer, or just flat angry at him for apparently not hearing you—especially if you’ve begged incessantly for something good, like a healing, conversion, or cure—something God would surely want, right?...

Read moreHow The Church’s Understanding of Suffering Makes Today “Good”

While some people balk at the Catholic Church’s teaching on suffering, it was precisely that theology—and its sweet relief to my soul—that pulled me back into the Church from evangelical Protestantism nearly thirty years ago. The Catholic notions of expecting suffering in life, turning toward the Cross and embracing it, and “offering it up” for redemptive purposes not only helped make sense of my own suffering, but changed my perspective on suffering entirely.

While some people balk at the Catholic Church’s teaching on suffering, it was precisely that theology—and its sweet relief to my soul—that pulled me back into the Church from evangelical Protestantism nearly thirty years ago. The Catholic notions of expecting suffering in life, turning toward the Cross and embracing it, and “offering it up” for redemptive purposes not only helped make sense of my own suffering, but changed my perspective on suffering entirely.

You see, somehow the message I received in evangelicalism felt like a hammer that nailed me repeatedly to the crosses of my life by implying the suffering was somehow my fault. Having spoken to a number of former Protestants about this issue, I know that my experience was not unique. Being told that reading our “Believers Identity In Christ,” memorizing Bible verses, or having more faith in Christ’s promises would cure our suffering only exacerbated it. I was extremely grateful to finally lay hold of the Catholic teaching on suffering, and I believe it must be unapologetically offered to a hurting world today.

Since it’s Good Friday, it’s a good day to consider a few of the Church’s salient points on suffering:

1. We will suffer!

Suffering is an unavoidable part of life, given the fact that we live in a fallen world where sin and death have been overcome by Christ’s death and resurrection, but have not yet been eradicated. Jesus said: In the world you will have trouble, but take courage, I have conquered the world. (John 16:33)

We live in a culture that peddles the lie that we are entitled to pain-free, pleasure-filled lives, and that suffering can and should be avoided at any cost. We are constantly encouraged to seek heaven on earth by quelling our hunger and quenching our thirst with the enjoyments of this world. But with life being what it is, we will all learn one way or another that “there is a heaven, and this ain’t it.” Living as though this is true benefits us in a number of important ways, including helping us avoid the inevitable addictions that occur when we compulsively try avoid suffering by making the pursuit of pleasure an end unto itself.

2. Suffering and death have eternal meaning.

Because of Christ’s death and resurrection, suffering and death have been given an entirely new and eternal meaning. Instead of dreaded curses to be shunned, the God-man transformed suffering and death into a portal of love and life, making suffering an opportunity to grow in love and death the hallowed entrance to eternal life. In other words, suffering embraced with love makes us grow up and learn to live and die for others, an all-important lesson we must learn if we are to follow Christ. Death, when welcomed with faith and hope, loses the sting of defeat and becomes instead the ultimate human victory. These critical truths need restating in a culture that endlessly seeks to avoid pain, aging and death.

3. “Offering it up” makes suffering redemptive.

While some Catholics roll their eyes as they remember being told to “offer it up,” there is profound truth to this quip. When we make an intentional decision to unite our suffering to the suffering of Christ and offer it as a prayer for others and ourselves, the prayer takes on supernatural potency and makes our afflictions a cause of rejoicing. Why? Because suffering, united to the infinite merits of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross, enables us to fill up in our flesh “what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ on behalf of his body, the church” (Colossians 1:24). What could possibly be “lacking” in the suffering of Christ? Nothing. Except its application to your soul and to mine—an application that occurs in time with our free cooperation. When we embrace suffering with love and offer it up, we expand our capacity for love by inviting God’s love to expand in us. This gives suffering powerful, redeeming value.

It’s Good Friday. A perfect day to remember that when the Cross presents itself in our lives, we can choose to turn and embrace it—even if it hurts—and let it bleed its transforming power right into our lives. I’d say that’s good news, indeed.

This article was previously published at Aleteia.

When the Crib Meets the Cross: Our Personal Adoption Story

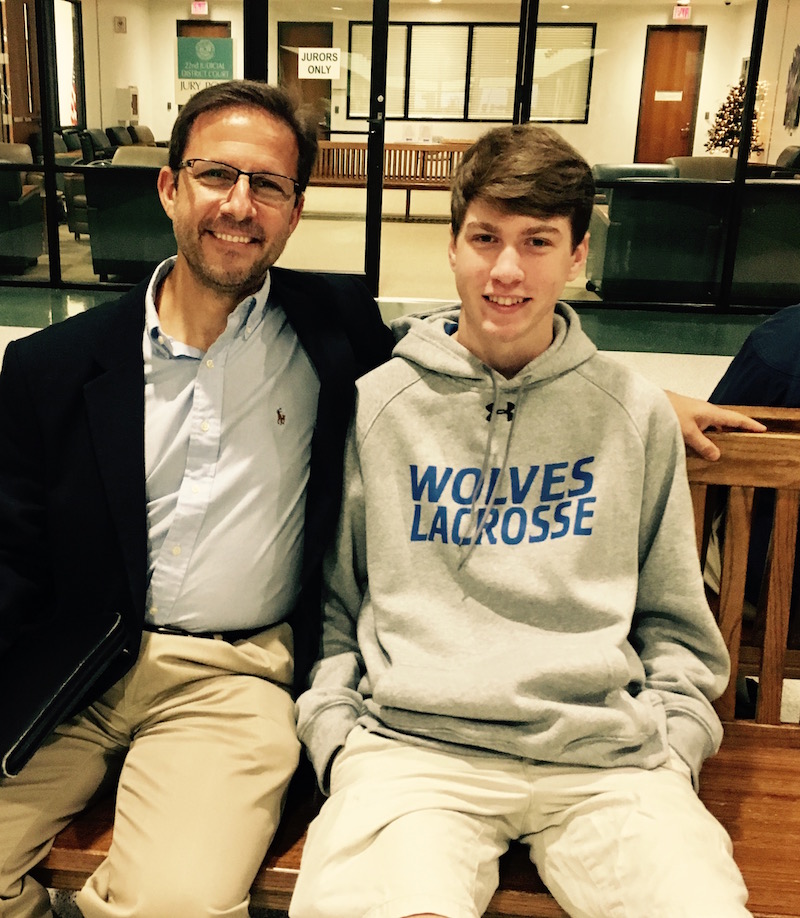

The minute the judge walked into the courtroom on December 5, I knew I was in trouble. What I had envisioned as a measured ritual of signing papers at the courthouse became an extremely emotional event when the judge, who surprisingly was a family friend, swore us in and asked for personal testimonies. Suddenly, I was weeping openly as my forever baby boy, now seventeen, sat beside me grasping my hand.

“Judy, can you tell the court why you want your husband, Mark, to adopt your son? And can you tell the court why you believe Mark will be a good father to Ben?” the judge asked kindly.

How could I explain to her that I had begged God to send a mentor and father figure into my child’s life, but that I’d never expected that God would answer my prayer with a wonderful husband, too? How would I convey in words the way I’d watched Ben latch onto Mark from the day he walked into our home, and how obvious it was that he’d loved Mark from the start? And how could I possibly articulate Mark’s generous, patient love for my beloved son—love that helped Ben find steady ground again after his Dad died months after he turned the tender age of nine?

After all, how do you put love, suffering and redemption into words?

“I knew your Dad, Ben, and he was a wonderful man,” the judge continued as the tears flowed. “And I know your family has been through a lot.”

Especially during December, I wanted to say.

December will forever be remembered in our family as the month a much-loved husband and father suffered a massive heart attack, never to return home again. In one fell swoop, December had morphed from the month of attending annual Nutcracker Ballets, decorating always enormous Christmas trees, and binge watching Miracle on 34th Street into the month of spending endless desperate hours beside a loved one labeled by doctors as “the sickest patient in Louisiana.” One seemingly insignificant day had converted December from the month of fresh piney smells, magical white lights and the sound of Christmas carols playing in the living room to the month of nauseating hospital smells, ominous fluorescent lights, and the never-ending clanging of life-saving machines attached to the hallowed body of a husband and father.

Here it was December again and we were standing in court recalling the pain of a crucifixion while beholding the glory of a resurrection, all at once. How could I explain that to the judge?

Because how can you possibly put love, suffering and redemption into words?

Love, suffering and redemption: they encompass the beginning, middle and end of the Christmas story. The story moves from a holy night to a holy Cross, from the wood of the crib at Bethlehem to the wood of the Cross at Calvary. In both places a Mother prays, knowing that only God can make a way for deliverance from the dark threats that surround life, believing that only God can somehow work things out for good.

I’d worried endlessly about Ben after his dad died, wondering who would encourage him, teach him, show him how to be a man? I’d felt the fear of what it could mean to be a fatherless child in a fallen world, begged God to somehow make a way for my son when I could see no path before us.

Mark literally showed up out of nowhere; having spent almost three decades as a missionary in foreign lands—many of those spent rescuing orphans from the streets and serving as a father figure to glue-addicted kids running for their lives from human trafficking. He had clearly heard God say it was time to go home to Louisiana, and though he didn’t understand why, he obeyed. Months later our paths converged in the tiny adoration chapel of our parish church and the rest, while they don’t say it quite this way, is holy history.

The wooden beams of our own crib and cross were transformed before my eyes by the wood of a judge’s gavel, as I heard her declare Ben “adopted” and Mark “father.” Indeed, I heard it as clearly as angels singing on high: love, suffering and redemption put into words—words made flesh during December.

This post appeared previously at Aleteia.

Pre-Christmas Special: Get signed copies of Judy’s books, “Miracle Man” and “Mary’s Way,” for a bundle price of $25 right now at Judy’s website at www.memorareministries.com. Free “Mary’s Way” Consecration Prayer Card included.

If The Cross Has Triumphed, Why Is The World Still A Mess?

With the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross having just presented itself again on the liturgical calendar, it’s hard not to wonder: If Christ triumphed on the Cross, then why is the world such a mess?

With the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross having just presented itself again on the liturgical calendar, it’s hard not to wonder: If Christ triumphed on the Cross, then why is the world such a mess?

During the past two weeks, I’ve wept over the news of a precious friend’s recurrence of beastly breast cancer, wept with a still-grieving friend over the loss of a loss of her infant son several years ago, and listened to a friend’s weeping heart over the agony of his son’s addiction. These friends I’m crying with and for? All great people of faith. All devout Catholics who deeply love the Lord. All seeking to look at the serpent that’s bitten to find life instead of death (Numbers 21:9).

For a long time, I believed that being triumphant as a Christian meant that life would somehow magically go well. I can still hear that peppy song we used to sing every Sunday at the little evangelical church I attended in my twenties: Abiding in the vine/abiding in the vine/ love, joy, health, peace, he has made them mine/ I’ve got prosperity, power and victory, abiding, abiding in the vine.

I bit into that message hook, line and sinker because I wanted to believe that faith could somehow produce a particular outcome from God, and hence assure me of some control over life. I wanted to believe that faith could guarantee good results, because that perspective made life seem less daunting and me more powerful. The rude awakening of learning the hard way that “the abundant life” does not equal a pain free life was itself extremely painful, but it compelled me to seek a new understanding of the meaning of the Triumph of the Cross. In so doing, I discovered the work of Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) who’s had plenty to say about the meaning of the Cross.

Ratzinger once wrote:

God’s compassion has flesh. It means scourging, crowning with thorns, crucifixion, a tomb. He has entered into our suffering. What does this mean, what can it mean? We learn this before the great images of the crucified Jesus and the Pietà, where the mother holds her dead Son. Before such images and in them, men have perceived a transformation of suffering: they have experienced that God himself dwells in the inmost sphere of their sufferings and that they became one with him precisely in their bruises. (Ratzinger, The God of Jesus Christ: Meditations on the Triune God, 53)

Truth be told, many of us believe that if we could just get rid of our bumps and bruises, then God would be with us. Or conversely, we think that if God were really with us, then we wouldn’t suffer so many bumps and bruises. But that is not the message of the Cross. Ratzinger goes on: The crucified Christ has not removed suffering from the world. But through his Cross, he has changed men. (Ratzinger, 53)

How, we want to know? How has God transformed suffering when he hasn’t taken away life’s pain? And how has he changed mankind through the Cross, when life on this Earth is still disordered?

By entering into the bowels of human suffering, Christ transformed suffering from a dreaded curse into a love offering that becomes the gateway of intimacy with him—a door through which he comes to meet us in our broken humanity. On the Cross, Emmanuel’s presence on this Earth finds its definitive meaning—the place where the deepest human anguish becomes the very locus of God with us; where he makes himself present in every God-forsaken experience of human life. Further, Christ asks us to embrace the Cross and let its triumphal resurrection fruit bleed grace into us—grace that enables us to stand in faith, hope and love in the face of life’s most formidable challenges.

It is instructive that the Church places the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows one day after the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross. The Mother of God, at the foot of the Cross, incarnates for us what “redeemed” suffering looks like. There she stands in travailing union with the God-man, uttering an acquiescent: Let it be done to me according to your will. There she stands in piercing pain, anticipating new birth, new life, a resurrection. There she stands with eyes fixed on Christ, trusting that love is stronger than death. The Crucifixion—his, hers, ours—thus becomes the place where each human being is intimately united to God.

It is not by eschewing pain and sorrow that we become victorious, but by inviting Christ into it that we receive the grace to perceive suffering as love, as gift, as triumph. And it is this very love—this self-gift—offered for others that turns wounds into glorified gashes in humanity capable of bearing great fruit. That is how the Cross changes us. And that is precisely where we experience its triumph.

This article was previously published at Aleteia.