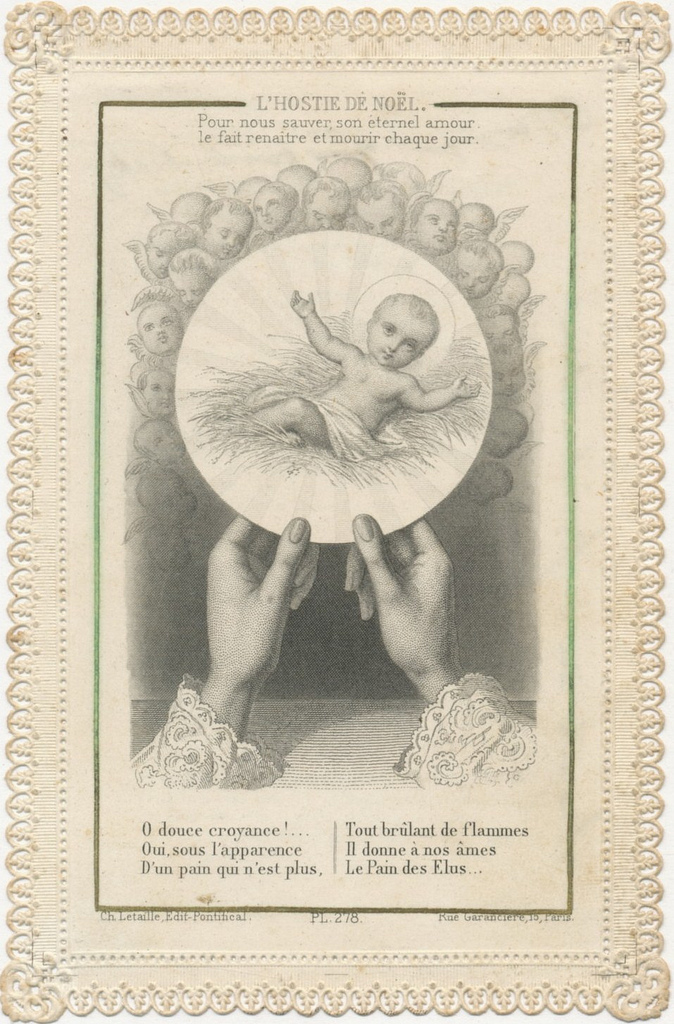

At morning Mass, the image of the infant Jesus repeatedly flashes through my mind as I ponder the innocent body of Christ in the manger while simultaneously beholding his broken, glorified Body among the people in church. As I think of his humble baby body—and his beautiful Mystical Body—it is as though I can hear his words ringing through time: “This is my body, given up for you.”

Having heard the stories of many of the daily communicants in church over the years, I can only marvel at the broken splendor of Christ’s Body; this Body on its knees in hunger and thirst, this Body famished for the Bread that alone can satisfy, bring divine comfort, give eternal hope.

I look around the church to see the humiliated woman whose husband left her for another lover, and the praying man whose mother died during his adolescence with a Vodka bottle pursed to her lips. Before me is the mystic father whose young adult daughter is fighting for her life against deadly cancer, and across the aisle, the holy grandmother who buried her husband and two young grandsons after the same devastating accident. And I hear his words:

This is my body, given up for you.

To my left is the devout teenager who recently became Catholic after her father opted out of their family, as well as the woman of God who holds the painful secret of a child given up for adoption while she was only a teenager. There’s the man ever on his knees praying to God for a wife dying of lupus—the wife he couldn’t get along with before the lupus struck—the same wife which he now sees, and every last day spent with her, as immeasurable grace and gift.

There beside the altar is the Christmas manger, but do we even begin to digest its meaning? Jesus, born in Bethlehem, which means “house of bread,” offering his innocent lamb-body as “the bread that came down from heaven”…the bread that he will give as flesh for the life of the world (John 6:51). Not coincidentally, Bethlehem currently bears the modern name of Beit-Lahm, which literally means "house of flesh”. The city of Jesus’ birth now unwittingly proclaims Christ-Bread as flesh indeed: true food, true drink—flesh for the healing of the world.

This is my body, given up for you.

One by one we process forward to “manger”—which means “to eat” in French—the blessed, broken Body of Christ craving the one Body that can make our brokenness blessed. We believe that it is his Body alone that can gather our poverty, mourning, hunger, and persecution into blessedness; the one true panacea that can provide the comfort, satisfaction, peace and belonging that we seek.

To my right is the smiling woman whose grandbaby is racked by an incurable disease, and the wise man whose daughter died of an overdose on Christmas Eve. I thank God for Christ’s Body, given for us as bread, as life, resplendently proclaiming the life, death and resurrection of the Lord until he comes again.

The Bread of Life, already present in all-holy omnipotence in the manger, is what enables us to see God in all things, including our wounded selves and stories. His Body empowers us to trust that we, too, can be taken, blessed, and broken—that we, too, may become hallowed flesh given as gift for other hungry souls.

Author’s Note: I have amalgamated the stories of the people in church to protect their identities and privacy.

This article was previously published at Aleteia.